Words and pictures. Images both literary and visual. These have been considered so similar that the verbiage used to describe them seem to be synonymous. Word pictures. A picture is worth a thousand words. Terms almost interchangeable. It should come as no surprise then that the devices we've made to construct words and images together seem to operate so similarly. Today, digital images and text files seem virtually the same, mere data, slung around networks of optic fibers and copper wires.

Looking backwards is often required to see forward. So it is when combining gelatin silver paper prints and typewriters; or, gelatin silver prints of typewriters, two technologies that seem so like-minded.

A few years ago, when I was delving deep into the world of paper negative photography - employing silver paper as a form of in-camera, black & white "film" - I began looking for alternative methods of displaying these as positive images. Two obvious ways were contact printing them, in the darkroom, onto other sheets of silver paper; or scanning the negatives to produce digital files, to be inverted later via software into positive images. Both methods have their benefits. The first produces a physical print, while the second is intrinsically software-based.

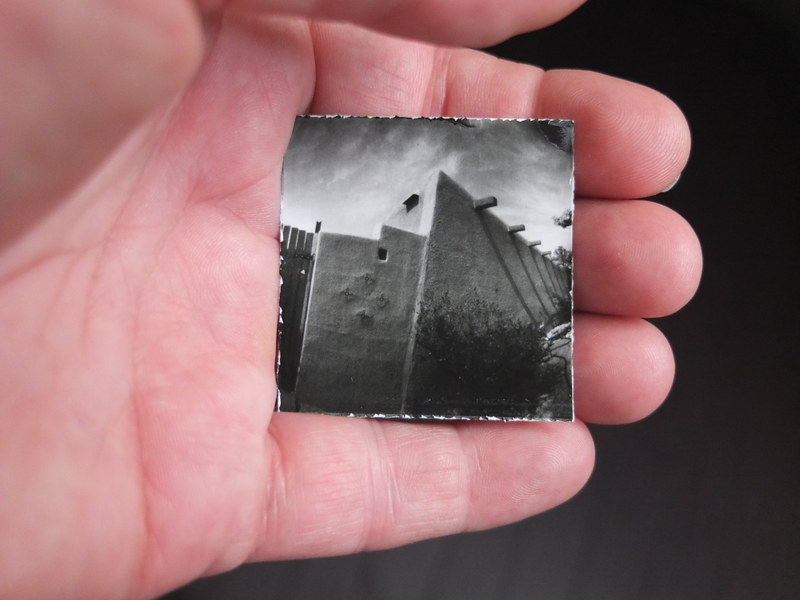

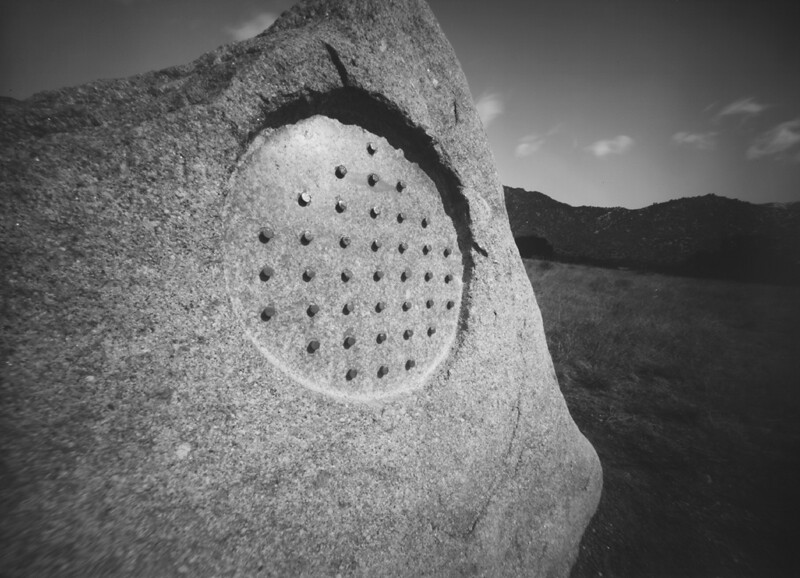

But then I came up with a third method, similar to digital scanning, but employing a handheld digital camera; placing the paper negative into some setting or scene, perhaps related to the original image, and often outdoors; photographing the paper negative within the larger scenic context; then inverting the tones of the image afterwards, to produce a positive monochrome image set inside an otherworldly appearing scene, a shifted color palette of negative tones, a reversed world where the real is imaginary and the imaginary real.

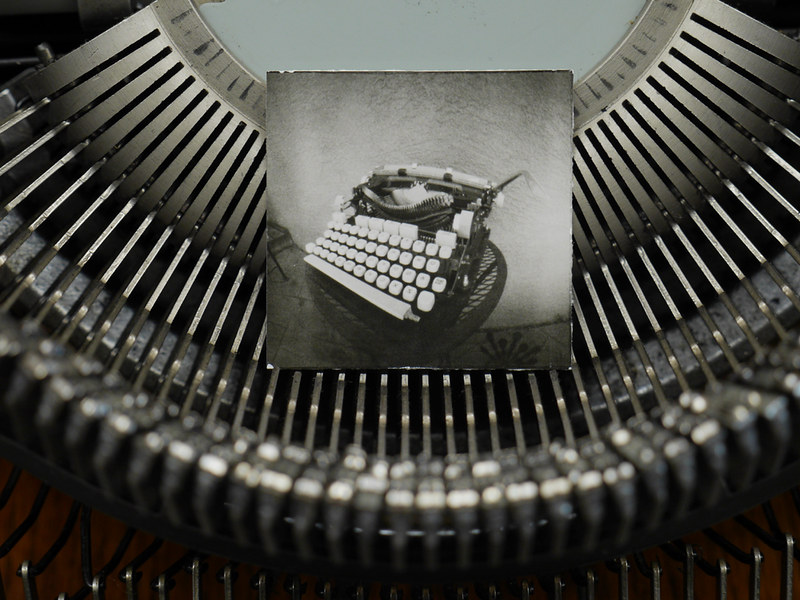

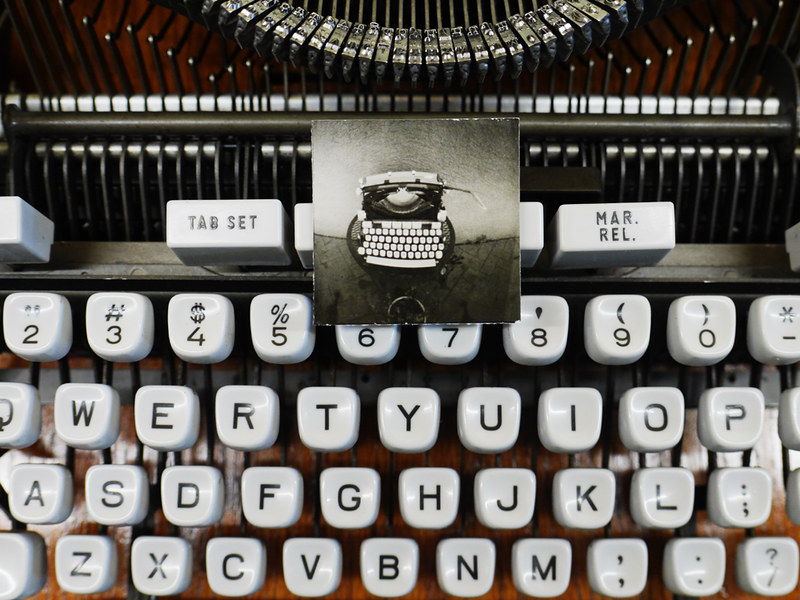

Since that time, I've been working more regularly with Harman Direct Positive paper, that produces a positive image requiring no tonal reversal afterward. But the idea of digitizing these prints, by photographing them in some larger context using a handheld digital camera, persists to this day. So it was that, after making this small study of my Hermes 3000 "Nekkid-Riter" chopped typewriter, using small squares of the Harman paper in my film canister pinhole cameras, it seemed obvious that sharing these prints online might be more interesting done this way than by merely scanning.

The process I use to make these prints, now that I've worked toward refining it, is so simple as to almost be silly. Give the paper a brief pre-flash of even light in the darkroom, then load into the film canisters. Rate the paper at an exposure index of 10, and the pinhole cameras at F/128. Meter the scene, make the exposure based on the metered reading. Load paper into a steel film developing tank, minus the reels, using loops of drafting tape on the backsides. Three such prints can easily be processed simultaneously. Mix Ilford MG paper developer, diluted at 1 + 15, to a volume of 100mL. Use continuous rotary processing, using the film tank on its side, for 3 minutes. Stop, fix and rinse as normal. Dry for an hour or two on a sheet of glass, taped down on the edges with more drafting tape. Done. Beautiful, individually unique gelatin silver positive prints.

I might say that the typewriters themselves, though each are as unique as the Harman positive prints, are a bit more complex. They aren't being manufactured, and spare parts are only to be found from other, donor, machines. Platen rollers can be resurfaced, and new ribbons are easily available, however. But the machines themselves are to be found online, at local thrift stores, Craigslist ads or estate sales. They almost always need some kind of service in order to be functional; at the very least, a thorough cleaning, degreasing and relubrication, then often some adjustments have to be made. Lots of hands-on fiddling, but also very satisfying when the typewriter collector/user also becomes a typewriter technician.

Typewriters also have a functional use, which is to mechanically print letters neatly onto paper. They're like film cameras in this regard, made to do but one thing, to lay down images of the literary kind. Which brings us back to where we started, with words and pictures.