I've been trying to get back to the print; the idea that a photograph isn't a photograph until you have paper in hand. I can remember, maybe 25 years ago, when that was the only type of photograph available, either a color print from a local lab or a black & white darkroom print I made myself. The idea of an electronic image was only possible for the common person back then if you had videotaped some photos with your camcorder and were watching them on T.V.

In the intervening years, all that has changed. Digital cameras and cell phones are so well equipped to enable the creation of instant electronic images that we forget about prints in hand. I know that I've been guilty of this, despite the fact that I still maintain a (somewhat primitive) darkroom in my unheated garage.

In the last decade since I've been dabbling in digital photography, I've certainly become lazier. The idea of shooting a roll of black & white film, then processing it, isn't so bad; it's the idea of printing every image in the darkroom that sets me back. Part of it is because my darkroom facilities are still so primitive - a small space, now crowded with junk, unheated in the winter and hot in the summer, requiring hours of prep time in advance in order to condition the environment sufficiently for chemical processing. Not to mention the dust everywhere, that ruins the idea of pristine, glowing prints.

I've pretty much relegated myself to the idea that, for capturing images out in public venues, I'm going to be using a digital camera. But I still like landscape and still-life images on silver gelatin paper. Fortunately, I've developed a method that seems relatively trouble-free and efficient, that produces nice fiber paper, silver gelatin prints.

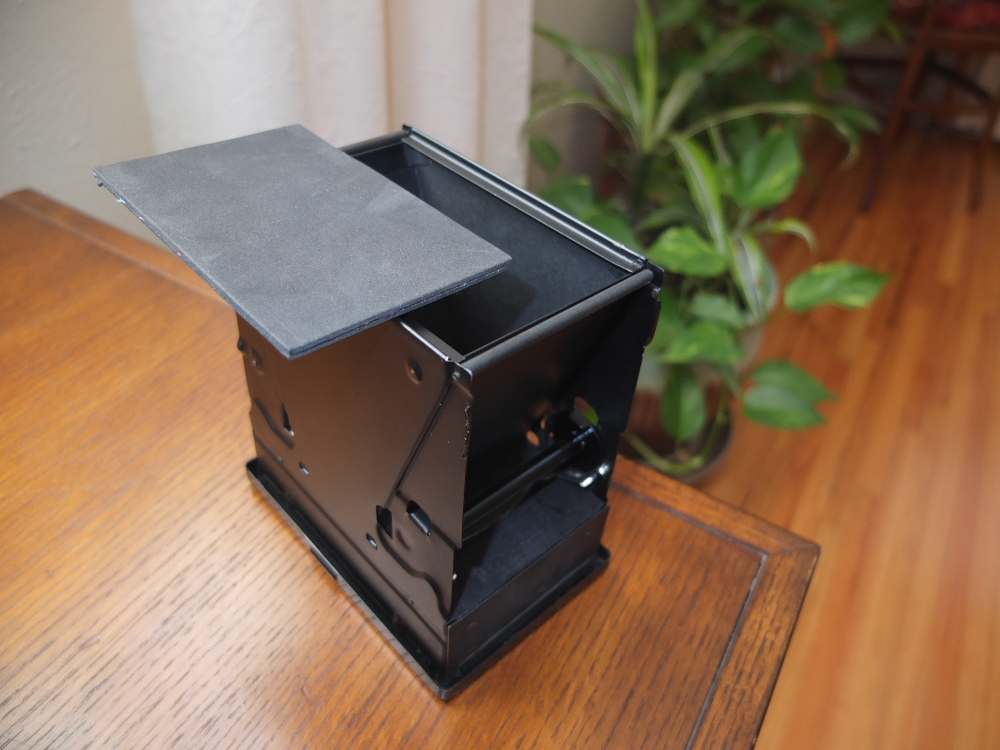

I load 4"-by-5" sized sheets of Harman Direct Positive paper into sheet film holders, expose them in either my Anniversary Speed Graphic or pinhole box cameras, then process them in the year-round convenience of my kitchen, via a Jobo print developing tank and rotary processing base. Once properly rinsed and superficially dried, I tape then to sheets of glass, using drafting tape, and permit them to dry in my film drying cabinet. After several hours, I have one-of-a-kind, fiber paper prints in hand.

Given the relative ease of this process, I can no longer afford to use the excuse that I don't have the time or energy to do this. So I've been trying, at least every week, to make some sort of image - any image, regardless of how mundane it might seem - using this process, as a means of exercising my processing skills and building a collection of these one-off prints.

Today's session was no less impromptu and spontaneous. The afternoon weather was balmy and warm, the winds calm, and so I set up tripod and Speed Graphic in my front courtyard and proceeded to load a sheet film holder with a pair of Harman prints. It's convenient that one sheet film holder holds two such prints, that can both be processed as a single batch in my day tank within the span of less than ten minutes.

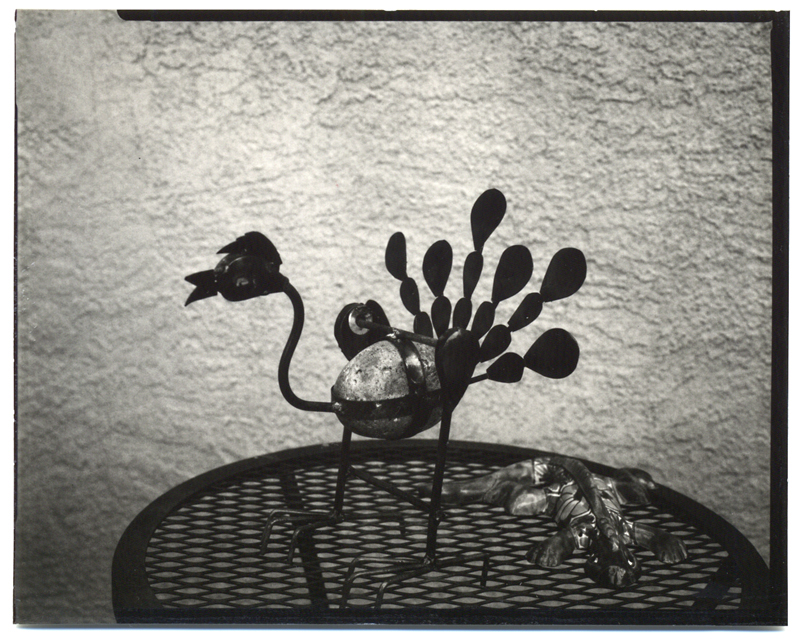

I thought this still-life of garden art sitting on a patio table was quirky enough to be representative of the kinds of spontaneous prints made possible by this process. And with the investment of just a bit more time, and a bit of gasoline, those two prints could have instead been exposed somewhere a bit more photogenic than merely around the house. But that's the beauty of this process - even if you don't feel like going far afield from home, you can still create these remarkable little prints, from scenes discovered just around one's own home.

What this really illustrates is the idea that it isn't all that hard to create two prints per week. That doesn't sound like an awful lot, does it? But two fiber paper, silver gelatin prints per week amounts to over a hundred prints in a year's time. All with the investment of just a few minutes time for loading the film holders, setting up the camera, making the exposure and processing the paper. Then a rinse - which I do under a tree in my yard, so as not to waste the water down the drain - and afterwards a few hours in the drying cabinet, while I'm off doing something else. Do that one time every week, and you'll have a hundred prints by the end of the year.

This process is made most convenient by the unique properties of the Harman Direct paper. While it does have some significant limitations that you have to get used to working around, such as contrast control, low sensitivity and spectral response, its main attribute is that you totally bypass the whole issue of processing film and the subsequent printing phase. What you're doing with the Harman paper is loading the finished print directly into your camera, then using a simple paper processing regimen. It really is a unique process, one that's also new, in the historic sense, given that such direct positive paper emulsions were unheard of in the formative years of photography. The irony is that this product has only come to market now, in the post-film era of ubiquitous digital imagery.

I would like to encourage you to embrace this process, experiment with it, and see what you can do. It's a great age we live in, where we have such a wide variety of choices available for our creative expression, including the choice of creating silver gelatin prints with such relative ease.