Yes, it's been almost two months since this blog has been updated, and in the meantime my callous disregard of my millions of readers has resulted in much hand-wringing and sleepless nights around the globe, I am certain. Please, let's do nothing rash and the global panic will subside.

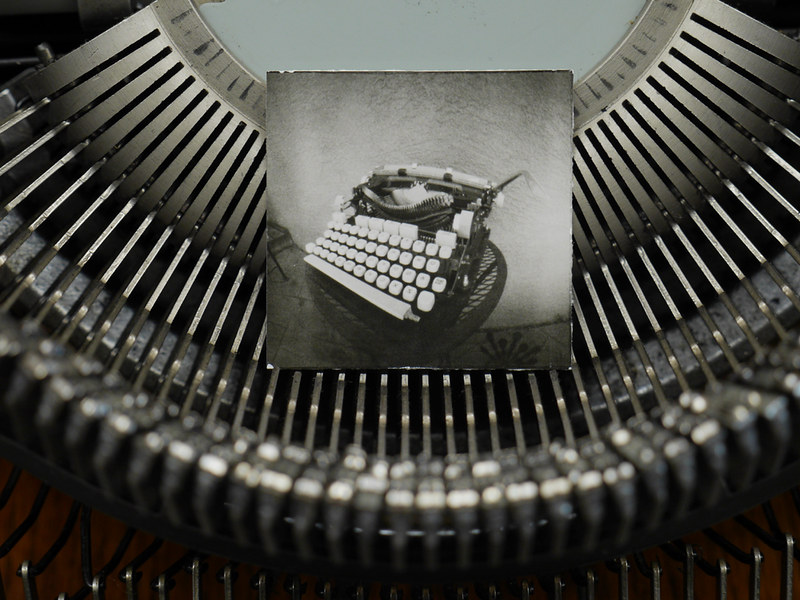

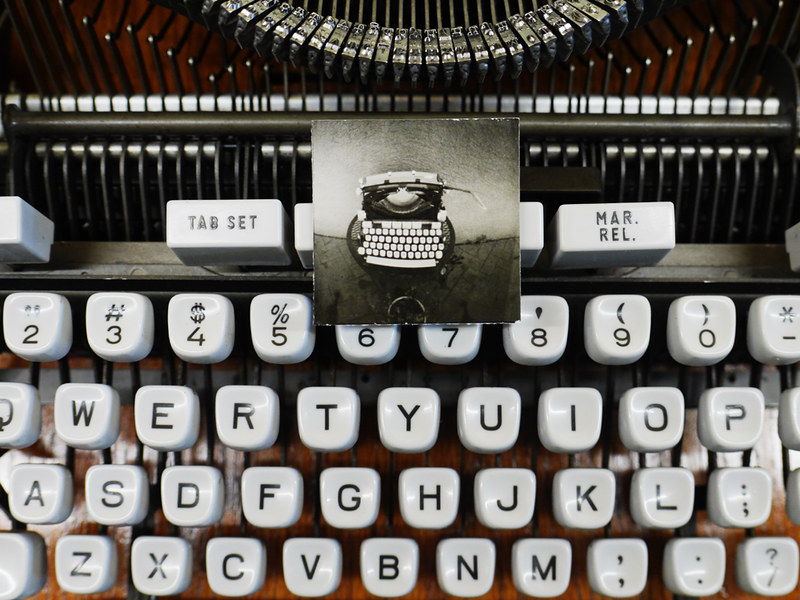

Though I've managed a few mediocre digital snapshots since then, I have experienced a complete lack of motivation or interest in gelatin silver photography. Part of this is due to the majority of my time and creative energy being spent on typewriter-related projects, such as my Hermes 3000 "Nekkid-Riter" and custom storage box, which has been covered in my other blog.

But within the last week I've had an interest in camera obscuras, most notably the small, handheld kind, that an artist might use as a tool for painting and drawing, rather than the room-sized, walk-in variety.

Camera obscuras can employ either a pinhole or refractive lens as the image-forming device, and as such fall into a larger category of related optical devices that I've dabbled with over the years, such as the "fauxtographic" viewing frame and the

pixellator camera (and its cousin, the

light pipe array), all of which I've employed as live-viewing devices, and would be appropriate subject matter for future blog articles.

Though I've also fashioned over the years innumerable pinhole and refractive-lensed picture-recording cameras, yesterday's project was the first time I've built a glass-lensed camera obscura as a dedicated viewing-only device.

I've come to believe that, in this image-saturated culture where most everyone carries on their person a picture-recording camera device of some sort, the very act of direct observation has been lost to the immediacy of constant recording. Billions of such images are now recorded every year, yet it seems as if the subtle nuances of the real world, from which these myriads of images have their origin, are lost to our present consciousness. We blindly go about our business of constant picture-taking while simultaneously being entirely unconscious to the reality of that which we're recording - or so it seems.

I'm beginning to suspect that what is needed in my personal photography is first an increased awareness of the visual world. My present modus operandi seems to be a hurried rush through some public area, blindly blasting away with my AK-47 of a camera while paying little attention to what's happening around me; as if I were more relying for success upon some happenstance, chance encounter with good fortune, rather than there being a purpose-felt dialog of exploration in a continual spirit of curiosity.

I'm feeling like I've been blind, having not yet learned to see.

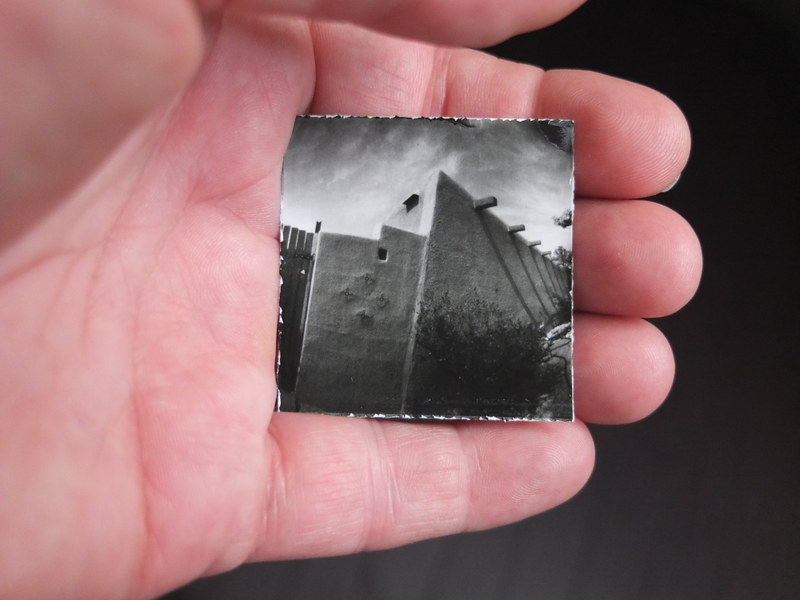

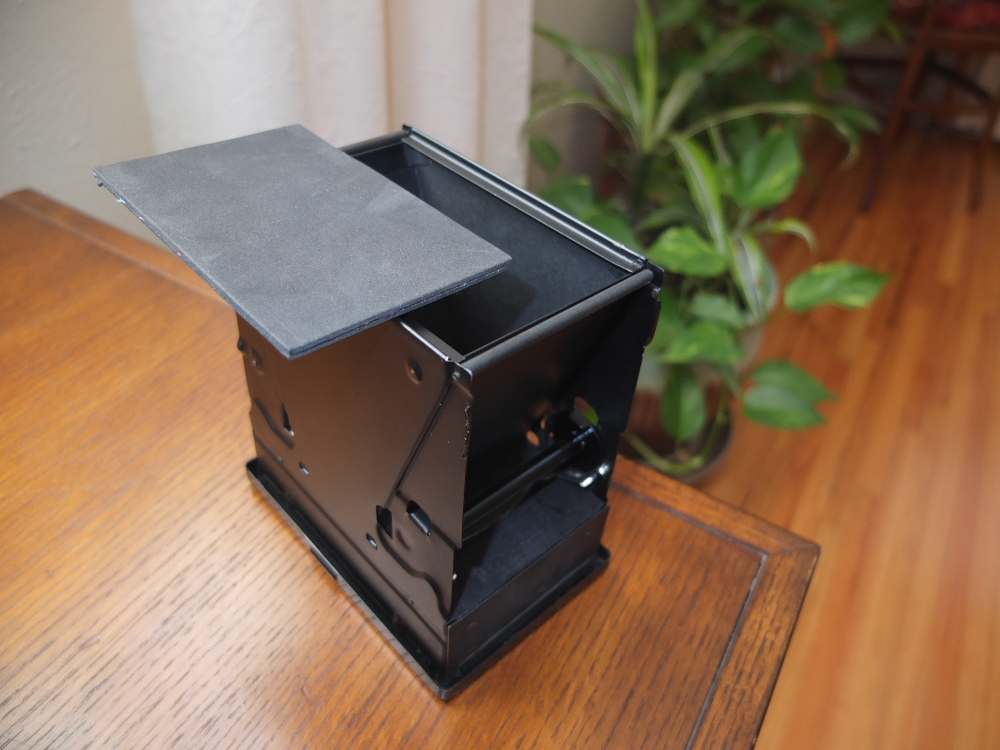

I've built this little handheld camera obscura as a device to gaze into, in order to learn to see more completely round about me. Peering down into its viewing hood at the five-inch-square screen below, what's presented is a live, full-color moving picture of the world in front of me, compressed down into a flat, two-dimensional image, complete with the optical effects of its lens, whose point of sharpest focus can be set upon objects far distant or close up, to within several feet even; much like looking into a twin lens reflex camera.

My intention is to use the camera obscura as a means for meditatively watching, rather than habitually recording. There will be no memory card or film holder full of the detritus of purposeless recording; rather, the images will reside in "wet-ware" as memories and recollections upon which to ponder.

TECHNICAL DETAILS:

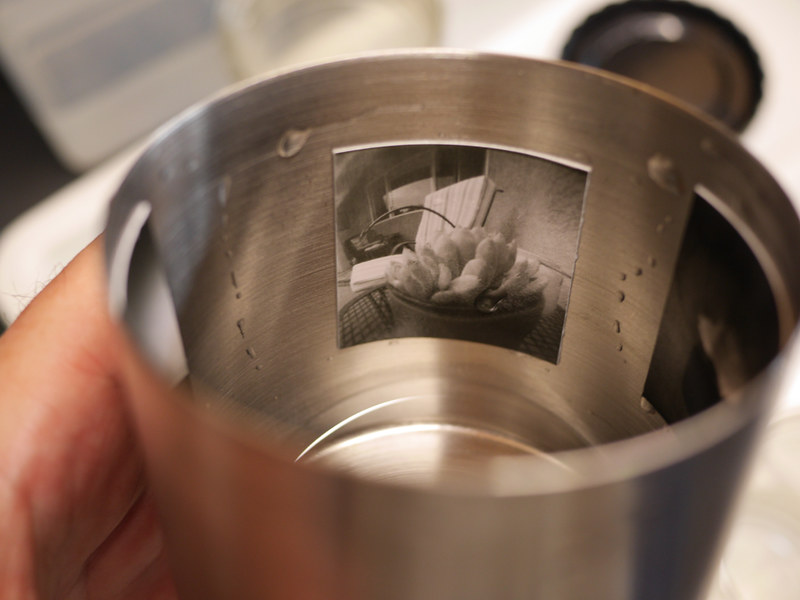

I've had in my possession for the last several decades a front-surfaced mirror, salvaged from an old projection television; which serves, along with a Kodak Ektar 127mm, f/4.7 lens, taken from a Graflex Speed Graphic camera, as the heart of the system. The viewing screen was made from a thin sheet of Lexan plastic, one side of which was ground down using fine emery paper on a random orbital sander. The body of the camera obscura is made from black foam core board, hot glue and gaffer's tape - the basic tools of the pinhole photographer.

A bit crude in appearance, perhaps. But with the application of some adhesive counter-top laminate or shelf liner material it could be made more presentable and weather-resistant.

It does remind me of that old Graflex SLR camera used by famed photographer Margaret Bourke-White, with its tall, chimney-like viewing hood.

There remains an acute similarity between the traditional camera obscura device such as this and the recent fad of "

TTV" -

Through

The

Viewfinder photography - where the view through a waist-level screen of a twin lens reflex film camera is rephotographed digitally.

OPERATION:

In use, the long hood places one's view conveniently located with the camera comfortably held at waist level, helping to eliminate most of the daylight glare. Though the handmade plastic view-screen serves quite well, it's not as bright as a commercially-made ground glass.

With the camera supported from underneath, the upper half of the camera, including view-screen and hood, can be easily adjusted vertically to selectively focus the image. Its default focus position, when fully down, is at infinity focus, with enough travel to permit a close-focus to within a few feet before ambient light spills in under the view-screen and washes out the scene.

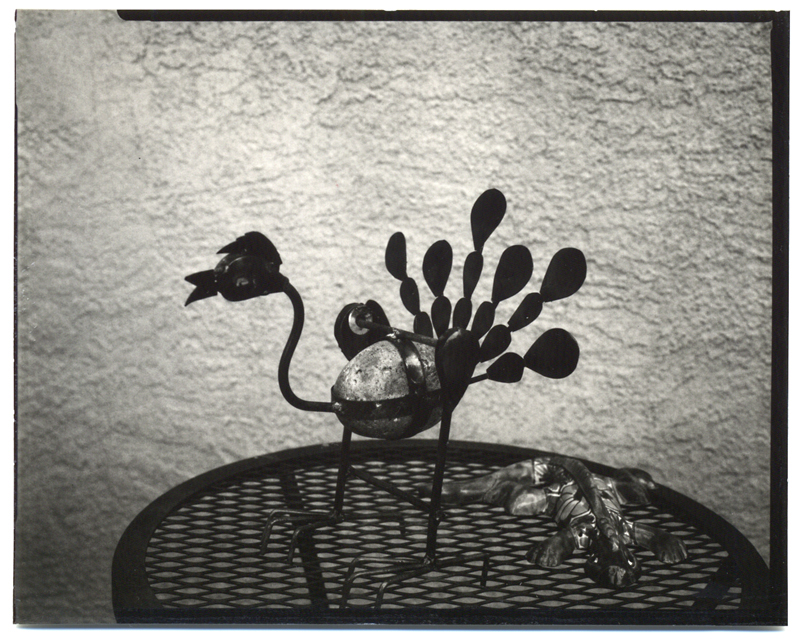

I use the Kodak Ektar lens with its aperture fully open to f/4.7, and thus there is evident in the projected image some artifacts of narrow depth-of-focus. Thus, using the camera obscura as a viewing/observation tool, one sees the world as a camera lens would see it, rather than the way human vision collages together multiple points of focus to synthesize visual reality.

Standing in my backyard, gazing down into the camera obscura, I'm able to selectively focus upon either the garden trellis in the foreground or neighbor's trees in the background, racking focus back and forth with gentle up and down movements of the viewing screen/hood assembly; almost cinemagraphically.

Though these simple elements that make up the camera obscura - lens, mirror and view-screen - are essentially the same as found on many photographic recording cameras, the experience is different from the typical large format view camera, because the image remains right-side-up (though reversed left-to-right), essentially the same experience as using a twin lens reflex camera but with the luxury of a much larger (5" square) image.

FURTHER REFLECTIONS:

In taking the camera obscura out to a public setting, I'd expect much the same kind of curiosity and reaction as one would with employing a recording camera, though others' reactions might be less pronounced were I to be found employing the device in the more innocuous activity of sketching, rather than merely observing.

Which gets to the point of a similar kind of device, mentioned earlier, what I call a "fauxtographic" viewing frame, very similar to the kinds of viewing aids employed by large format photographers and film makers in photographic previsualization, but with the added feature of a clothes pin clicker device that serves to mark the "decisive moment" by simulating the firing of a camera's shutter.

I had independently co-invented the viewing frame, not for the purposes of aiding photographic composition (though it does serve that purpose admirably) but as an instrument of public performance art, as a kind of social commentary, or even protest, in counter-reaction to post-9/11 America's documented phobias over the act of public photography.

I was curious to deconstruct this phenomenon. Was it the mere act of human observation that was deemed objectionable, or the more specifically photographic act of placing borders around a specific point of view, then isolating it in time with the click of a shutter?

Skeptics might argue that there's no deeply-thought-out conspiracy at work against the philosophy of public photography; that in these times of heightened tensions and increasing concern over "security issues" one can never be too careful - just go with the flow, keep your head down, pay your taxes and just you no never mind. It's a small price to pay to be safe. Whose side are you on, anyway? Say, you're not one of them there Elk Hiders, now are you ... ?

No, I'm not one of them there Elk Hiders. But I do think about the act of photography, at its most fundamental level, as being a literal extension of the act of seeing. A photograph most essentially represents a simple human gaze, frozen in time.

And so, any objection to public photography is really an objection to direct human observation itself, disguised under the rubric of "security". It's not enough that we shouldn't photograph in public; what's really being asked/insinuated/demanded of us is that we not pay any attention at all to what's really happening. Keep your head down, your eyes averted and your mouth shut. And don't think too much, it'll just get you in trouble; not what would be required of responsible citizens in a (supposed) democracy, since (in theory) self-governance requires continual observation of the elected by the electorate.

With the portable camera obscura, however, it's not a device easy to carry or conceal, like the fauxtographic viewing frame. It's big, black and draws attention to itself. More importantly, it's not an instrument intended for social commentary, but a tool for a very personal kind of visual exploration, a device for learning to see all over again.

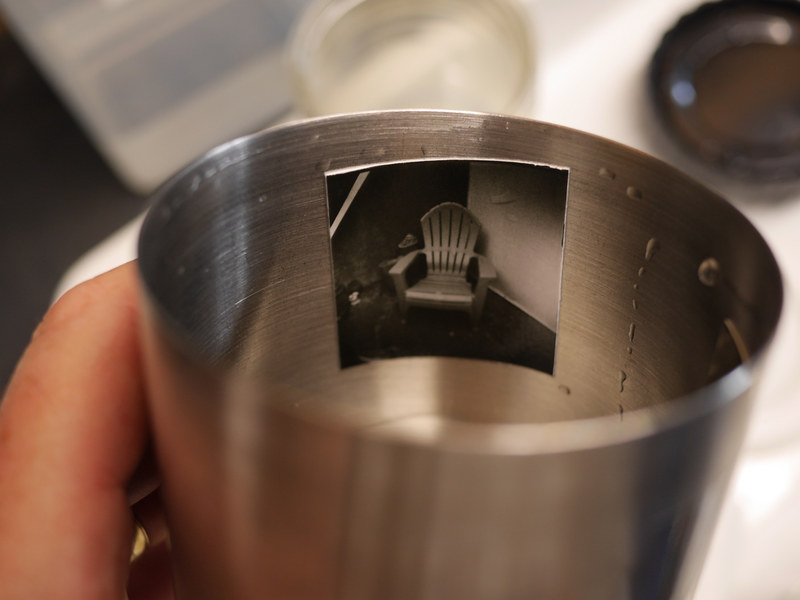

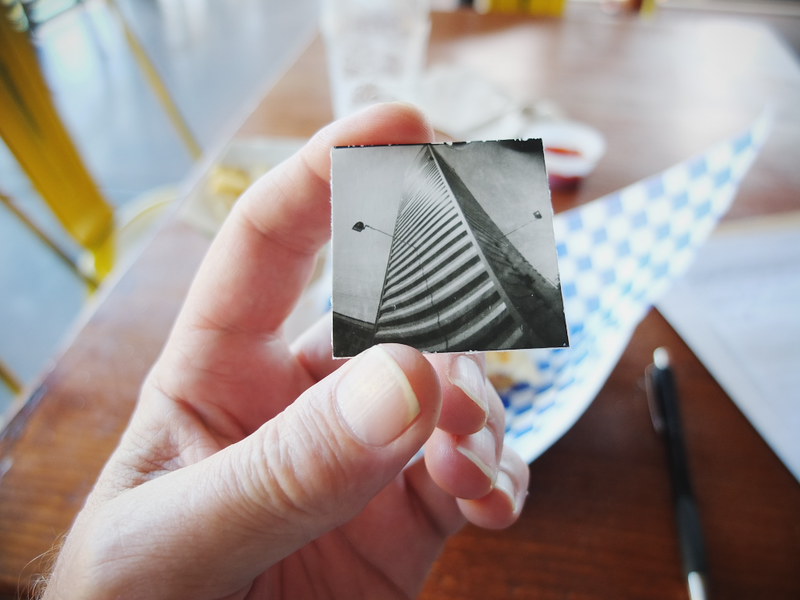

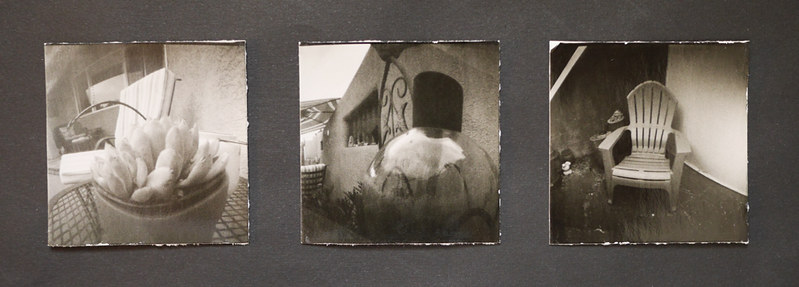

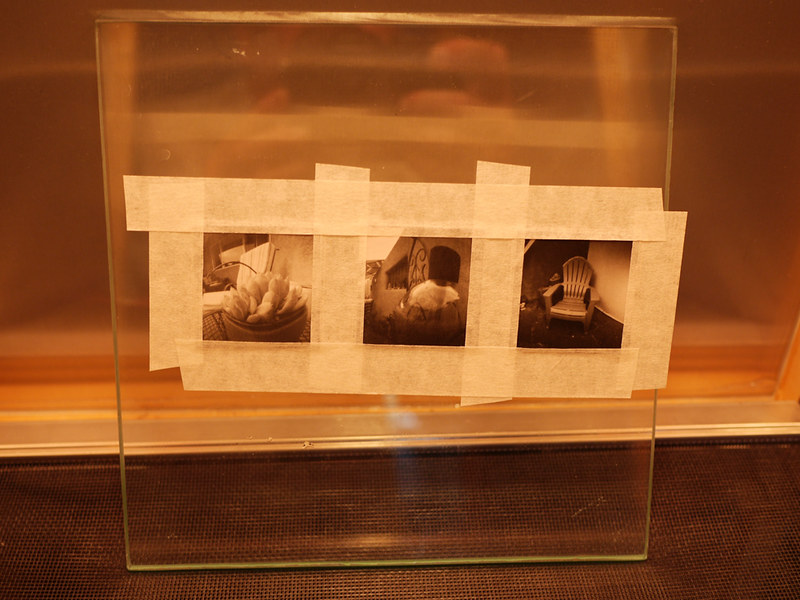

Post-Script: Though I've included three digital snapshots of the camera obscura's view-screen as an illustration of the kind of image it makes, it in no way is convenient or practical to do so, given my ready availability to other, better-suited photographic devices. I see these example images as the photographic equivalent of typecasting a manually typed page - it provides the viewer a reasonable facsimile of the original, but in no way is intended as a substitute for the live, physical artifact.

An even simpler version of the camera obscura is possible, if an upside-down image were of little consequence, that being to dispense with the front-surfaced mirror and project the image onto the back of the box. This opens up the possibility of cobbling together such devices from commonly accessible materials, such as magnifying lenses, plastic sheets and any sort of box-like enclosure. And gaffer's tape. Don't forget the gaffer's tape.