I

It might seem almost a cliché to say this, but sometimes one has to lose something in order to gain something else. Or, to paraphrase another adage, out of loss comes new beginnings.

No, I'm not referring to some personal tragedy; I've lived a rather sedate life, if truth be told. No, this has more to do with the idea of lost opportunity, of the promise of unlimited creativity squashed by life's inertia, perhaps.

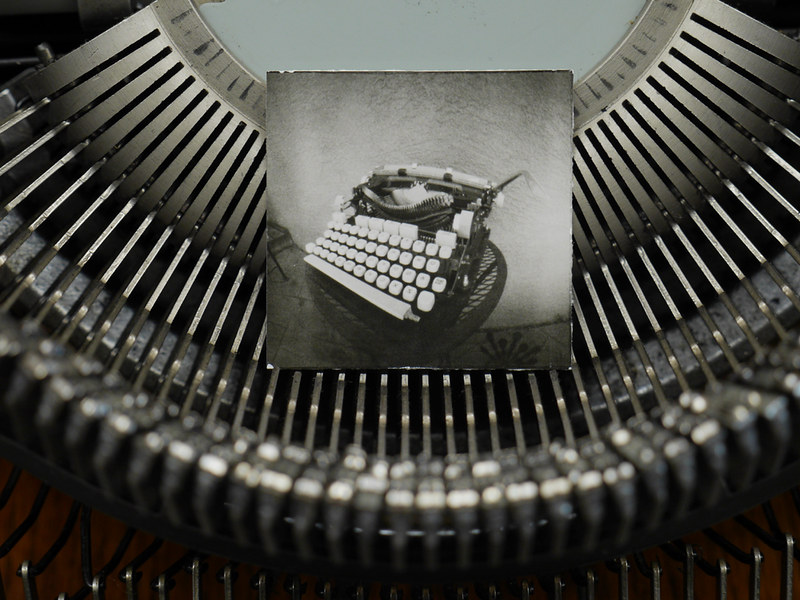

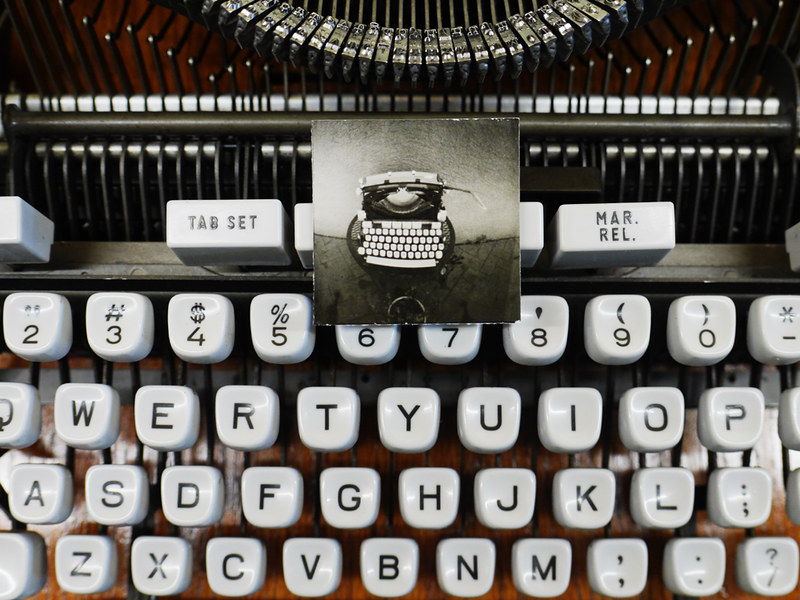

Some time ago I had created a

video for my You Tube channel, within which I made mention of, and demonstrated, a small, brass pinhole box camera, designed to make small images onto two inch square pieces of photo paper or film, taped to little brass film plates that fit into the camera via a changing bag. A humble little camera, it had seen much use about a decade ago, and promised much more, but since then has been relegated to the storage bin, acquiring the patina of disuse. Alas, such is life, so full of opportunities missed or squandered.

But then something curious happened. One of my video's viewers had recently contacted me, inquiring about possibly purchasing a copy of said camera. Thinking it over for a day or two, I finally decided that, rather than try to recreate a one-off camera design, why not just sell this very same camera? After all, it wasn't getting much use any more, being stowed away for all of these years, its last use only a distant memory in the back of my mind. I had recently been thinking about what to do with this sizable collection of pinhole cameras I've assembled over the years, that are no longer getting regular use, thinking of perhaps giving them away to some local school's darkroom program, if they'd have them, but never made any progress on the idea. In this newfound opportunity, I sensed that perhaps something better could come of it than what I would ever have accomplished on my own; the person wanting to buy it is a graduate photography student and aspiring artist, and so I am flattered to see this little gem of handiwork get a second lease on life in the hands of someone much more creative than myself.

But first I had to clean up the camera a bit, it being spotted and blotched from years of misuse; a thorough cleaning would prepare the brass surfaces for growing a fresh new patina, representing a true second lease on life. But also, I wanted to test out the camera a bit, to make certain that it indeed still worked as advertised, and also for the opportunity to include a few sample images along with the camera when I shipped it; I had never before used it with

Harman Direct Positive Paper, and was anxious to try it out. I also wanted to experience working with it one last time.

In deciding to make these test images using the Harman paper, I was reminded that normally I wouldn't use this paper in a pinhole camera, due to its extremely slow speed in cameras whose focal-ratios might be well into the hundreds, which in my past experience has required extended exposure times, even in bright sun, of well over a minute or two. But this little camera has a focal ratio of only F/140, sufficiently fast to permit an exposure time of only 15 seconds or so in bright winter's daylight.

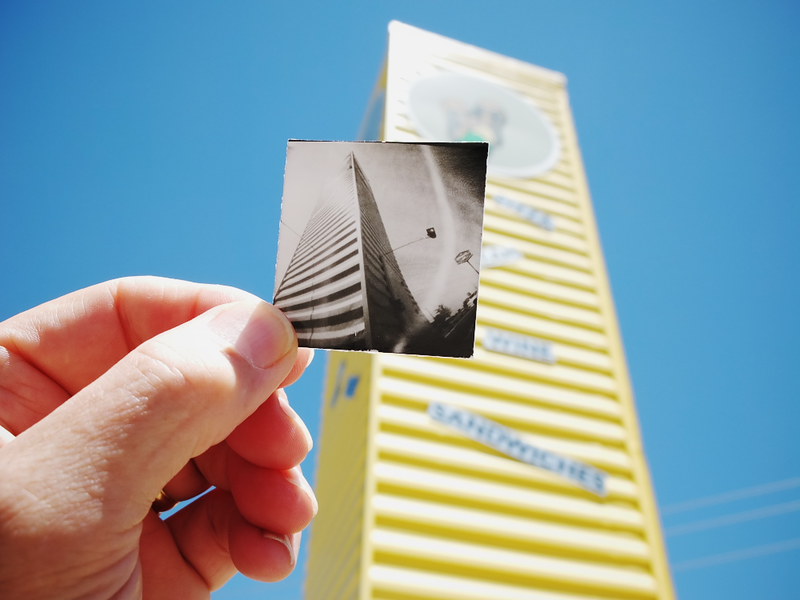

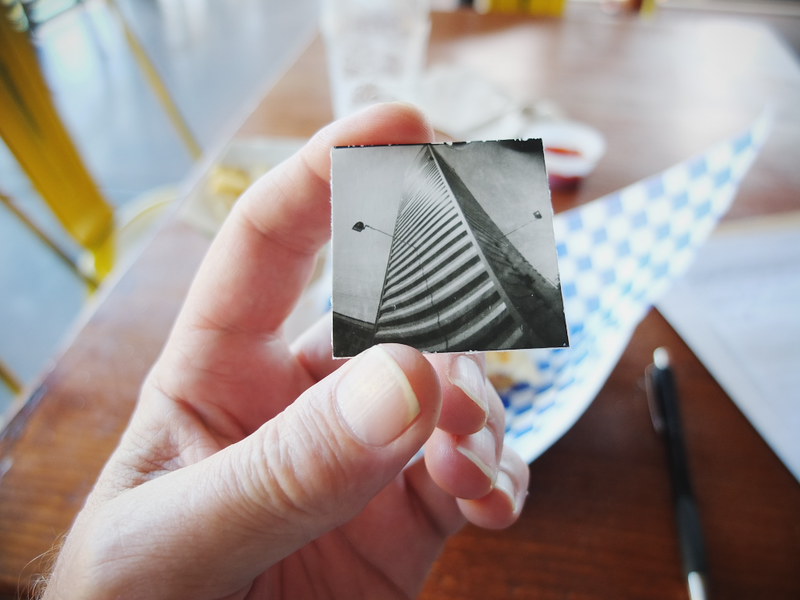

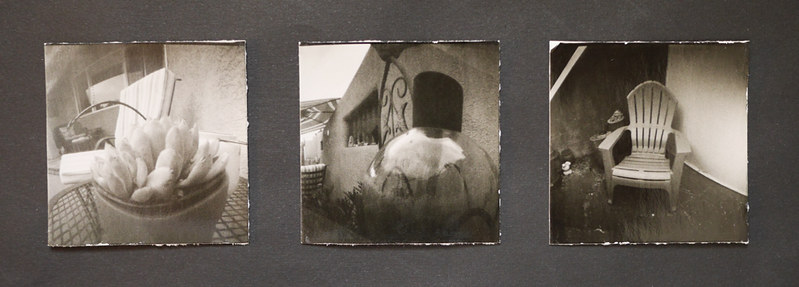

The resulting prints startled me in their quality, I must admit. No, I don't really have seller's remorse; I'm happy to see this camera go to a better home, where it will, at long last, see its purpose in life fulfilled. But in the process of letting go of it, I had gleaned a newfound appreciation for how beautiful a small, well-crafted direct positive pinhole print can be. These images are small, certainly, but also sharp - startlingly so; enough so that one would be hard pressed to tell that they had been exposed in a pinhole camera at all.

This last week I've been preparing the camera for shipment to its new owner, including making a wooden base upon which the camera can be mounted securely to a tripod, and through this process I began thinking deeper about these pristine little prints produced by this humble brass box, thinking that perhaps I need to dig out of the storage bin another small-format pinhole camera (or, dare I say it, make yet another?) and try my hand again at more of these diminutive direct positive prints. There's something intimate and personally familiar about these small, 2" square images; they don't cry out for attention with some ostentatious artistic pretension, like mural-sized prints in today's photographic galleries might; they're smaller than what one might view on one's own smartphone, even. You hold them in your hand, nestled in your palm ever so delicately, like a dried leaf or dead insect, and peer into them in wonder, like artefacts of some lost archaic process, up front and held close to one's self. They're small enough that you have to expend some effort in comprehension, but not so small that you need a magnifying glass.

I can see displaying these little prints matted to an oversized frame maybe eight or ten inches square, big enough to isolate them from their surroundings, to give each one the space they might need to breathe their own life and find their own context, with the help of the viewer's participation.

By the end of this week, this little camera will be forever out of my hands, hopefully in better charge of someone more intent on photographic creation than I; but what I've gained in exchange is a newfound appreciation for the power of small, pristine quality pinhole prints, and for that I'm grateful, considering myself richer for it.

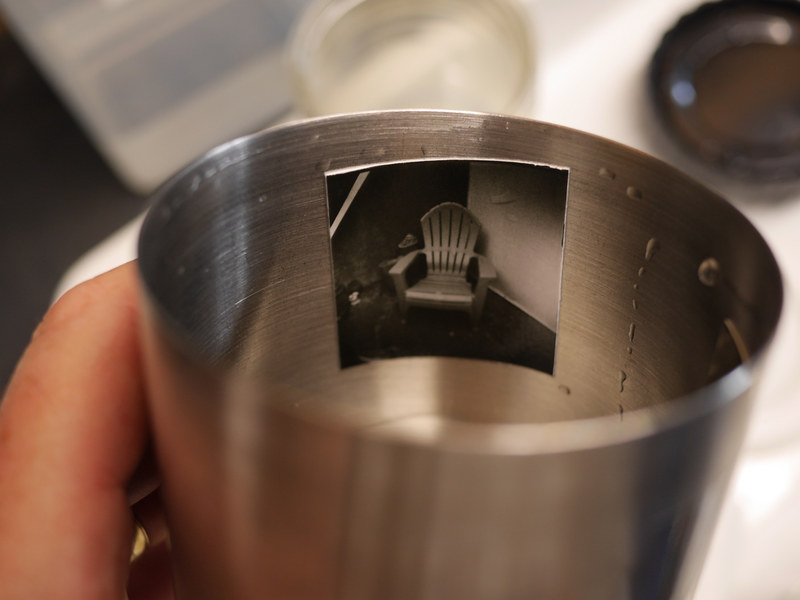

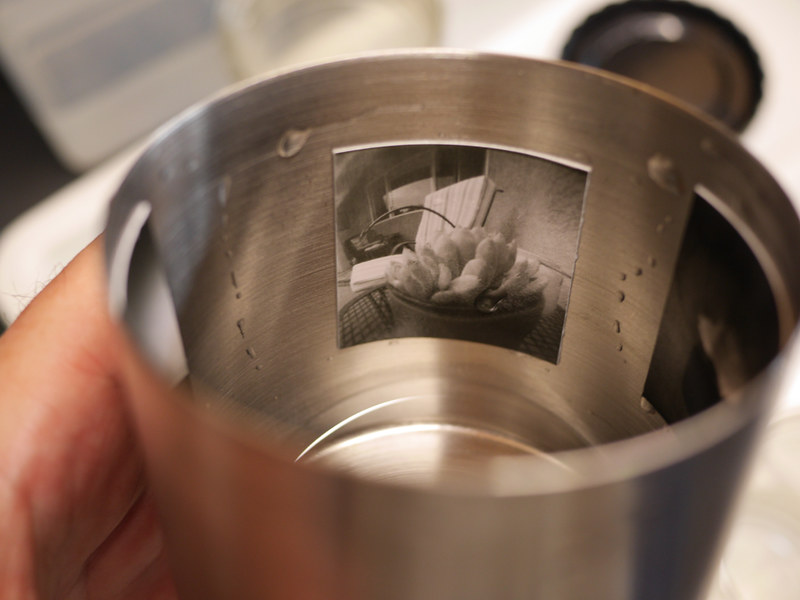

A technical side note might be in order, pertaining to how I develop these little prints. Yes, one could easily do so in open trays in one's darkroom. But my darkroom these days is chilled by winter's cold, being located in an unheated garage, and so I prefer the convenience of using a developing tank in the comfort of my warm kitchen.

Those of you who've seen my You Tube videos might know how I do this, but for these small prints it involves taking a small metal 35mm developing tank and adapting it for use as a makeshift rotary processor. For one or two prints, I will keep the metal reels inside the tank and insert the paper, emulsion side facing inward, in the gap between the outer edge of the reels and the inside surface of the tank. Two such prints can be thus positioned, opposite each other so any potential movement won't cause them to overlap and interfere with their processing.

For three or four prints at once, I will remove the reels and apply little loops of painter's masking tape to the inner side wall of the tank, which will hold the prints into position, evenly spaced for processing.

Only 110 milliliters of chemistry are required for processing; I will typically use Ilford Multigrade or PQ paper developer concentrate, diluted "1+10," meaning 10mL of concentrate into 100mL of water. Once the prints are mounted in the tank and the lid installed (requiring a changing bag or darkroom), the chemistry is poured in through the lid of the tank, which is then positioned on its side and gently but continuously rotated for the duration of the processing time. This particular volume of chemistry is more than adequate to process four prints at once, while being insufficient to cause the liquid to slosh out of the lid while being oriented sideways and rotated. In a rotary process, instead of the tank being completely filled with chemistry, as you would with roll film, you only need this small volume, enough to just periodically submerge the paper as the tank is continuously rotated.

It helps to have a roller base upon which to spin the tank; while automated systems can cost thousands of dollars, and you can purchase a manual Jobo roller base for upwards of $50 or more, it's possible to make such a manually-operated base yourself, using parts readily available from the hardware store, which I'll cover in a subsequent article and/or video. But even without a roller base, you can simply lay the tank on its side and slowly rotate it on your kitchen countertop; use a cutting board or other thin piece to elevate the body of the tank far enough above the work surface so that the lid of the tank overhangs the edge of the board, with the opening pointed over the edge of the sink in case of spills, permitting it to rotate easily, while remaining level. Also, a terry cloth or similar dish rag on the cutting board can often help the tank rotate easier.

I have three such stainless developing tanks, and have noticed that two of them leak slightly from the edge of the lid when placed on their sides and rotated, and so I only use the third tank as my dedicated mini-rotary processor; if yours leaks, just take the necessary precautions.

I should mention, when working with fiber-based print paper such as Harman Direct Positive, of the need to adequately rinse the paper after processing, in order for it to be considered archival; otherwise the fixer chemicals will remain within the paper fibers and, over time, degrade the paper; because of their plastic coating, RC papers have less of an issue with this, but Harman Direct Positive only comes in a fiber paper version. For this reason it is advisable to use a rinse aid after the fixer and initial rinse, to help shorten this required archival rinsing time and conserve water.

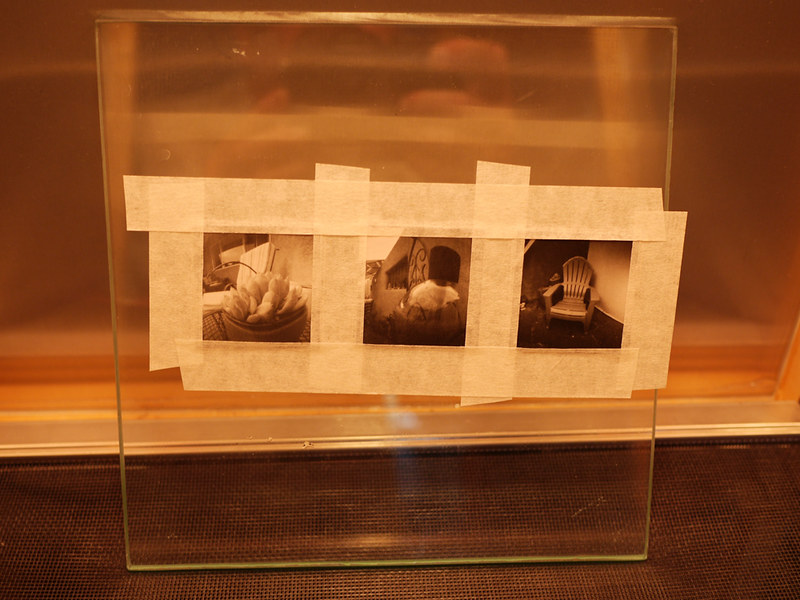

After the final rinse, the paper needs to be squeegeed off so its front and back surfaces are just damp, then use a hair dryer to dry those surfaces; the inner paper will still be wet, however, and thus the paper will need to be thoroughly dried. When doing so, fiber-based paper has a tendency to severely curl toward the front side of the paper, due to emulsion shrinkage. To prevent such curl I will, after squeegeeing and blow drying, tape the prints face-up to a sheet of glass, using drafting or artists tape along the very edges, then place it in a warm, clean area for several hours. Periodically check on the paper and, if needed, reattach the tape if it starts to peel up from the glass due to the paper's curling. If done properly, you can get fiber prints to dry very flat using this method, without the added expense and bulk of a dedicated print drying machine. Making do and improvising is the secret to success with these legacy processes.

It's difficult to adequately describe the joy I experience when I open up the developing tank after one of these short 10-minute processing sessions and behold these pristine little gems still wet in my hand. It's something about their diminutive size and unexpectedly sharp appearance that gets me every time. I invite you to experience the joy of pinhole photography for yourself, the rediscovery of new beginnings.